The horrific time for me was when the bombs were coming down

Liverpool Girl Not long after the war started a lone raider came over. We were in the street and I could hear these bangs. There was three boys from the Army in the street, home on leave, and all I could hear was this Bobby Henderson shouting “Quick! Get the kids in, that’s gunfire!” I’d never heard gunfire in me life, so we ran in, but no bombs dropped. It was twelve months afterwards before we saw any bombs.

East London Girl This was the first bombed area, Custom House. We got the first bomb in the war, in Cundy Road. (1) I was going to get some eels, some jellied eels, up at old Jack’s. In the summer he used to have an eels stall and sell ice-cream. I went up there with the basin in me hand and a new pair of stockings on. All of a sudden there was a great big crash and I run home and dived down the shelter. I tore me stockings and from that day to this I never found that basin or the two bob!

Her Mother It came on a Friday night. (2) I had a piece of fish on the electric stove on the Friday night. We were going down to see the kids – they were down in Somerset – and I had a load of fruit all jarred up. We got bombed out. We had nowhere to go.

East London Woman I was living in Selby Road, Plaistow. They were nice little four-roomed houses, but there was no real garden. A lot of people had built one Anderson shelter between two houses. (3) Some of the women would ask me into one of their Anderson shelters, but not being there long I didn’t really know anyone well enough. It probably saved my life, not knowing them well, because when my house got bombed I was at my Mum and Dad’s in Odessa Road. (4) Frank, my husband was on late turn. I got a bit nervous being on my own, though you always thought it wasn’t going to happen to you. I said to Frank “I think I’ll go over to Mum’s. Don’t bother to come home if there’s a warning, go in the nearest shelter.” This was the arrangement we had.

I went ’round to Odessa Road and the next morning Frank comes in the door with the cat in his arms. It didn’t register. I said “What’ve you brought the cat ’round for?” “Well”, he said, “this is all you’ve got left.” Had I been there and gone under the stairs, I wouldn’t have stood an earthly. Your first reaction is that you’re so pleased that you’re both alive, that neither of us was there. When I went ’round and saw it I knew one or two of the people that had been killed and injured.

Another time, during the bombing, at one end of Odessa Road, by Forest Lane, they had built their Anderson shelters so that they backed on to one another. Very friendly – six people had done that. And a bomb hit the middle of them. Someone said “I shouldn’t go and have a look if I was you”. But I had to go and look. I couldn’t help it. Ooh it was horrible. I saw someone’s brains down the side of a crater. A woman there, she was never well again after that. A headless body was over her bannisters and what shook her was that the headless body was a boy she knew. ‘Round Eric Road, Fowler Road, they had a bomb one day and my Mum went ’round there and looked. She came back and said “Ooh, I wish I hadn’t gone ’round there. They’ve got them all lying out on the pavement, covered over. You can see their legs.” You knew you shouldn’t go, but you still had to go and have a look.

Stepney, East London Boy One reason I developed a real hatred for the Nazis was Lord Haw Haw. (5) His real name was William Joyce and he broadcast on the Deutschland Rundfunk. You’d never worry if you missed Churchill on the radio, but you would worry a bit if you missed Haw Haw. He was compulsive. You had to hear him!

Stepney, East London Girl People used to go mad in the shelters when they listened to him. He used to say “All you people down there by the Free Trade Wharf, we’re going to bomb you tonight” – and the people would go mad!

Stepney, East London Boy They used to put him on as a joke. That’s how it started. He would say “This is Lord Haw, This is Lord Haw Haw,” – he brayed like a donkey – “We know you rats are in your holes. We’re coming to blow you out of your holes in the East End.” He’d say “Do you know the Coop in Mansell Street? Anyone listening in there” – (that would be your shelter) – “You’ve had it tonight. You’re going to be blown to pieces.” You’d laugh at first, but a lot of things he said came true. He’d say they were going to bomb Z Shed, so and so dock, and the next morning it was bombed. So you might listen to hear whether you were going to be bombed. You thought he was a right rat, but people still had him on.

Stepney, East London Girl Every night.

Stepney, East London Boy It was a sort of masochism. Around about quarter to nine. But all this stuff about Churchill’s speeches on the radio being morale boosting is utter rubbish. A lot people had no time for him.

One night when I was taken to the shelter I found a bug, not that I hadn’t known bugs before, but I really objected to an unhygienic place where there were hundreds of people, and although I was young my feelings about Churchill were expressed through-out the shelter along the lines of “that dirty no-good bastard is sleeping in a beautiful bed tonight – why am I not?” I think the average person thought as much about Churchill as they do about Callaghan. (6).

Stepney, East London Girl Nobody took much notice of him.

Stepney, East London Boy But what was uplifting was a programme which we heard every week in the shelter called Into Battle. It always started with the Lilliburlero. The Lilliburlero was originally a tune that was specially written against the Stuarts, but they regurgitated it against the Germans. It was terrific – really stirring tune. This programme really was morale boosting. They would play the tune and then they would tell you of an incident on one man’s war that week – like a parachutist was shot out of his plane, his parachute was burning, he came down in a small village in France, eight Germans tried to capture him, nevertheless he killed them all, and he was spirited by the underground back to England. Another morale booster were the concerts in the shelters. Someone would get up and sing. It was really great. And then of course you’d have the propaganda, constant propaganda which were total lies.

You would have a raid where the whole district would be shattered and everybody demoralised. Then on the news they’d tell you how many planes had been shot down during the raid – totally exaggerated. It has since been proved by officers of the ack-ack that some evenings they didn’t shoot any down. Then there would be the propaganda films, which showed us that we were all equal!

It would generally be a soldier who was on leave or ready for some heroic action. He would come home and go to the local village pub and meet a young woman who happened to be the squire’s daughter, and the squire was a Brigadier of the ’14 – ’18 war. The soldier would then be class-conscious, in that he was a bit frightened because of the snob value the English have. But he would find that this Brigadier is not only human, but he goes fire-watching, he’s in the Home Guard, he only has one egg a week – just like everyone else! All these films were like that.

Stepney, East London Girl They were terrible. We used to go to the pictures three times a week. It would come on the screen if there was a raid on, but very few people would leave their seats. The majority would stay and watch the film.

I had to be an air raid warden. They made me go in the ARP. Don’t kid yourself it was all voluntary!

London Woman I don’t know whether I had to – no, I must have had to, because I never volunteered for anything. We had to go and learn about fire-watching, in the Fire thing. We learned all about it and the Civil Defence.

London Clippie I had to be an air raid warden besides working on the buses. I had to go and dig all the people out of the bombed houses. I was at the back of Stratford when they went. I stood with a boy and we watched six of his family brought out. He’d just got to the ARP post and this bomb got his house. They made me go in the ARP. Don’t kid yourself it was all voluntary!

London Lad Firewatching? When I was 15 I used to have to get up at 2 o’ clock in the morning after working all day in the factory and walk through the blitzes to go and bloody fire watch in the factory. That was very annoying that was. Didn’t like it, but we had to do it.

2nd London Lad I joined the Auxiliary Fire Service. They had boys. You worked two nights a week. You were messenger boys. One of the great attractions was you got to wear a steel helmet, and you had a bike. I didn’t have a great heroic career though, because I deserted my bike in the middle of an air raid and took shelter. Fuck the Fire Brigade.

Arran Farmer The nights of the Clydebank Raids (7) there was an incendiary bomb dropped on the island. They were coming overhead, over the island – a terrible racket, hundreds of planes coming over. Some appeared to be coming in and some appeared to be coming out over the island. On the second night of the bombing, which was the worst, there was a heavy mist, and the whole mist was flickering, right across the channel, and all our windows in the farm were rattling. It was a hell of a night. Goodness knows what those people in Clydebank went through.

Glasgow Girl I wasn’t frightened. I’ll tell you an odd thing. On one of the nights we ended up sitting in a cupboard in the house and I was knitting a very intricate pattern of a jacket. I made an awful lot of mistakes from time to time, and I had to rip it out, but on that night I sat in that cupboard and I knitted the whole back of it perfectly without a single mistake. It must have been a nervous reaction. I would certainly say that I wasn’t upset as my mother was. She was much more nervous. For a younger person there was a sense of excitement about it which takes away the fear.

Glasgow Lad When I was in the Home Guard, a machine-gun company, we had a big hall where we kept the machine guns, and obviously we had to mount a guard on it. It was myself and another two young chaps, we done the guard nearly every night in the week. We couldnae get volunteers! It was also the same in the area that I worked at the time, with fire watching. They couldnae even get firewatchers. I used to do that too, at times, finding that we were the only people bothering to turn up. When I joined the Home Guard I was excused from quite a bit of that.

I was carrying this coffin. Sometimes two kids in a box and you could actually hear them rattling backwards and forwards in the coffin. I was sickened with the whole situation.

During the blitz on Glasgow our Company was called to a densely populated working class area in Blackburn Street (8), where a land mine had apparently dropped. When we arrived there the entire area appeared devastated – smoke, flame everywhere, and you could still hear the screams of people in the wreckage. Our first duty was to cordon off the area, to keep hysterical on-lookers (mothers, fathers and others) away. They were scrabbling in the wreckage searching for relatives. It was to save their own lives partly too. We also got the job of taking the names of people reported missing.

Incidentally, despite the resolute speeches by people like Churchill and the rest – what they were going to do to Hitler when ever they got him, and chin out and stomach in, Victory signs and all the rest, when the bombs started to fall on Glasgow, rather than the people running out into the street shouting defiance at the bombers, in this particular area dozens of women with their children ran out into the street yelling and praying to God to stop it now. They were so hysterical some of our Company had to drag them from the street and shove them in closes, or warn they’d best get into shelters.

But on this particular occasion one of the reasons for people getting hysterical was that about three hundred, four hundred yards away there was a cinema, the Capital cinema, which was always open and continued its shows, even during the bombing, and had sing-songs. It’s a sad reflection, right enough, on some of the parents, but lots of mothers and fathers obviously thought nothing would never happen in their area. They’d maybe had a bevvy and they’d stayed on in the place, and it was only when they heard their area -Blackburn Street – had been bombed that then they came out searching for their families. We were taking names nearly all through the night.

We were standing with our rifles and bayonets, keeping the people out, it was that bad. I was carrying this coffin. Sometimes two kids in a box and you could actually hear them, rattling backwards and forwards in the coffin. I was sickened with the whole situation. There was nothing anybody could do. There was just hatred in me. I wanted to fight against people who could do this to working class men, women and children. This affects you, you know. I joined the army without showing any birth certificate. I was 16. I said “Give me a gun, show me where they are and I’ll kill them.”

Stepney, East London Boy In Wapping a parachutist came down and apparently he was partially blinded. he’d obviously bailed out of a plane. He jabbered away to the people gathered around him, in some foreign language. They assumed he was a German and they smashed him to death. They killed him. They learned later he was Polish, a Polish officer, which was tragic because he was like a British fighter pilot. This is common knowledge in Wapping. Many, many people will substantiate it, but of course none are prepared to say they took part in it or saw it happen.

When the bombs were falling on the village there were terrific bangs. My parents said “It’s giants trying to get in. Don’t worry though, the door’s locked”

Ist London Boy As a youngster I used to walk around in the blitz. I never bothered, even with shrapnel flying around. On one occasion I was working in a tailor’s workshop in Cleveland Street, near the Middlesex Hospital in the West End, and all of a sudden they dropped a bomb. I was in the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade and I went to the Middlesex Hospital and they had people with eyes hanging out. I went in there and helped as best as I could. Yet it didn’t frighten me. I never used to bother going in an air raid shelter.

2nd London Boy At the beginning I went to the Anderson and then to the public shelter, but even with the raids every night you saw everything wasn’t completely devastated, so you got contemptuous after a while. You got used to it. I lost my fear. I got bored.

3rd London Boy It was common to walk along a street and shrapnel would be flying around you and when you got indoors you wouldn’t even mention it. In fact, there was a lot of bartering of shrapnel and other war mementos. If you got a fire bomb intact you were well in!

London Girl The only really horrific time for me was when the bombs were coming down. That was quite frightening, but when we went to the underground shelter that was a bit of fun and a bit of excitement. You didn’t feel so isolated in a community shelter.

Stepney, East London Girl I’d been sent out to see where there was some water, ‘cos they used to turn the water off, because of the bombing, and I passed this policeman and I found out where the water was. I got the water, and I was on my way back to my Mum where we lived and this unexploded bomb went off, and the policeman all went up in bits, and all the glass came down on me, and I went into hysterics. My shoulder was a bit cut, otherwise I wasn’t hurt, but I was shocked. This Doctor says to my Mum “Get her away.” I’d been through all the bombing, but this was one of the worst parts. I’d never been evacuated because my Mum didn’t want me to go. I didn’t want to go either. She said, if I was going to be killed, I’d be killed with her, where she could see it. Lots of Mums felt like that. But the Doctor said I had to go, because of my shock. I was taken down to Bournemouth. It was an orphanage. They just took me in as special, they didn’t have any other evacuees there.

They was all middle class kids. They all spoke properly and did everything properly, and I was an outsider. I was there for six months. They didn’t treat you bad. They gave you everything you needed. But I fretted so much, lost weight – there was nothing wrong with the place, except I wasn’t one of them. And they were orphans. They didn’t have anybody, and I wanted to be home.

Somerset boy I used to watch the bombing over Bristol from Pensford police station. My father was a policeman. It was a lot of pretty bright lights, and then when the bombs started falling on the village itself, and I was indoors – it was so bad we couldn’t go out to the shelter – and my parents said “It’s giants trying to get in. Don’t worry though, the door’s locked”. And I never bothered at all.

We didn’t have any air raid shelters. They hadn’t been built. We used to go down the steps and underneath the tunnel and take turns throwing bricks at the rats.

Liverpool Teenage Girl It was mass murder for those twelve days of the May Blitz. We were living near Mount Pleasant at the time. There was one place – it’s Edge Hill College now, in Daley Road, but then there was another college, corner of Clint Road. There must have been at least 400 killed that night. Underneath this college was an air raid shelter. People from miles around used to go there. It got a direct hit with a land mine. The boilers burst, the people were scalded. A brother-in-law of mine was working for the Corporation, he was on the rescue operation and he come to our house and he was sick, really sick. He said “They’re putting old people’s heads on young people’s bodies” – trying to piece them together. They got that many out, and it was so bad that they just threw quicklime in.

One night when the May Blitz was at its height there was five hundred planes over Liverpool, and we had no airforce. Do you know what they had to try and combat the planes? They had anti-aircraft guns going around on vans. You were more frightened of them than anything else.

London Electrician I was working and living in Liverpool at the time. By the third night they ran out of anti-aircraft shells, they were so poorly equipped. They had to send a destroyer into the beginning of the docks because Jerry was trying to blitz the docks. The destroyer fired a line along the docks to keep Jerry off the doings. Jerry had collected a hell of a lot of our land mines which had been abandoned at Dunkirk, and he developed a technique which was bloody awful if you were in it. These flaming planes came in with one landmine under either wing and they systematically bulldozed by aeroplane. I dodged the last bastard, the last night they were there. They dropped one quarter of a mile away from me and set fire to Morelands match factory. A hell of a lot of timber went up and there was a big black ball of smoke coming over. Although the destroyer tried to protect the docks they bulldozed Bootle, which was the living area for the dock workers. They came in with no opposition.

It was so bad in Bootle that bridges across canals, and water, electric, gas, drains, the whole bloody lot was schmozzled. You couldn’t go through any of it. The people either had to get out of there or…. – I met one poor bugger I knew, who’d been blitzed. He’d been bombed out and I met him three months later. He’d been living amongst the rubble, never going to work. Never anything. His face looked like a rat. I’d never seen a man look in such a state. He really was a nervous animal and his eyes appeared to be trying to look behind him all the time. The shock of such a bashing – the bomb had smashed his house and he’d lost his wife and kids – he’d just gone beyond. I couldn’t believe it was the same man. It was some time before he became normal again.

I had an Alsation dog at the time, which never came upstairs. I felt this weight on me legs. I woke up and saw the dog. “What’s up, Stalin?”

Bootle Docker, former Communist Party member I was bombed out in Trowthy Street on the Saturday night. I had been working all day Saturday and I didn’t finish until 6 o’ clock on Saturday night. I decided to go the Royal and have a pint and sit down. There was a lady sitting there having a drink. She said “Aren’t you Joe Byrne? Didn’t you used to live in Akenside Street?” “Yes I did”, I said, “what’s your name?” “Caveney”, she said. “Oh, I know you. I know your mother. You used to have a little job for your Mother – take me Father’s suit to her on a Monday to put in the pop shop and get it back on the Saturday”. I stopped there about half an hour. Got her a drink. Came home. I was with Mother at the time (my wife and kids were in Wales, evacuated). Went upstairs and got me head down. I had an Alsation dog at the time, which never came upstairs. I felt this weight on my legs. I woke up and saw the dog. “What’s up, Stalin?” And then I could hear Mother downstairs, groaning. I came down and said “What’s to do?” “The air raid! It’s terrible” “What!” I’ve only got one good ear and if I sleep on that I can’t hear a thing. I said “I’ll go and have a look ’round.”

We had a door dividing the living room from the back kitchen and when I went to open it the bloody thing wouldn’t open. It had jammed. I forced it open, went into the yard and had a look around. I looked to see if the warehouses at top were on fire, because I’d said to Mother “If you see those on fire, get out of the road, move – that’s the target area. Once they get a fire started, all around gets blasted”. I looked up but nothing was happening. I went in and sat down in an armchair. Mother says “I’ll make you a cup of tea.” I says “Don’t worry. Sit down, I’ll make it.” I goes into the back kitchen. Gets the kettle for water. But no water. I thought “Bloody hell.” And then the lights went out.

We’re in the dark – well, not quite dark – it’s like a summer’s night. I goes in the parlour and puts a shilling in the meter. Come back to try the lights, but they’re not working. So gas has gone, water has gone. We’ll have to do without the tea. She’d put a nice white tablecloth on the table and cups and saucers. The next thing there was a bloody fearful rattle. I stuffed her underneath the couch, and then the bloody windows came in, and tons and tons of soot were falling down the chimney, and splattered all over the place and over me. I sat in the chair with me good ear up and me bad ear down. And then I heard them” “Hear we are, here we are, here we are” – that was the drone, just like “Here we are, here we are.”

By the Cunard building there was a fireman with a little wee pipe which was dribbling water. It struck me “By Christ, this is the preparations they have!”

The beam above me fell down, right across me and I got cut. I’m underneath this beam and I hear a voice in the far distance, so it seemed to me. “Oh my God, get me out of here, the blood’s running all over me.” And it was coming nearer and nearer and nearer and it was Mother underneath the couch, and it was my blood going on her hand. I was bleeding and hadn’t been aware of it. I said to her “I’ll find an air raid shelter.”

The people next door were away and their air raid shelter wasn’t being used. I went out into their yard and it was bloody levelled – just a heap of bloody bricks. I climbed over them and their shelter was alright but there was no door on it. The door had been blown off. I told Mother to stop there until I came back.

I walked down the entry. All the back walls had fallen down. I climbed over them all, to Peel Road where I had a brother living over a butcher’s shop. When I gets there he’s got all his family and somebody else’s family in their shelter. I told him that Mother was alright and that I needed a dressing for my cut. “I’m going along to St Leonard’s Church, there’s a dressing station there.” I left him to go back up and see Mother. I went along Peel Road and when I got just past Grace Street – St Leonard’s Church – the church was ablaze. No fire-engines in sight. But by the Cunard building, which is next to it, there was a fireman with a little wee pipe which was dribbling water. It struck me “By Christ, this is the preparations they have!” I said to the fireman “Get down off there. You’re only acting the goat. What do you think that’s going to do? The building’s on fire!” The water was being pumped all the way from Akenside Street out of the Rimrose Brook. There was no water in the borough. They’d busted the mains at Strand Road, where the railway bridge is. The electricity comes across, the gas comes across there. They’d busted the lot.

I got back to Mother’s. We had no home, so I left with Mother and we walked down to me sisters. When we got in we were filthy. They had no bath. I said “Will you give Mother a hand? Clean her up and put some different clothes on her.” I said “I’m going down to the beach to do my swilling”. I got no dressing on the wounds. Salt water done it. There was no dressing stations. Grey Street was burnt out, and St Leonard’s was burnt out. All the emergency things were all knocked out.

A tent was put up in the North Park where dockers, me and all the others, went for our dinner and tea break. That’s where we went. There was nothing on the docks. You couldn’t work on the docks – only clearing up the debris, that’s all. I was working for Ellerman’s. The tent was set up by the council with Government money. The tent was there all during the blitz until a week after and then they opened a shop in Stanley Road and you went there and got your cup of tea.

The kind of shelter they built in the streets was built of mortar and sand – lime and sand. They just fell down. They didn’t need anything to blow them down

Before the blitz I was after the Haldane shelters. (9) I knew Professor Haldane had made this Haldane shelter and I made an application to the Town Clerk in Bootle, to have a discussion with him, to get it done. I met him and he told me “Haldane will be in Bootle next Sunday.” There was a crowd of us there who felt like me. They were going to hold the meeting in the hall, but there was so many people turned up the Minister said “Come in the Church. I’ll give you permission to use it.” They put Haldane in the pulpit and the Church was really packed. Haldane made a very, very effective contribution. A feller called Johnny who was a councillor raised the matter in the council and the council got busy on it. They decided to ask for plans.

We did have a situation where some wise guy – I don’t know whether he was a government man or not – but he met me and several members of the NUWM (10), along with shopkeepers and other people, and his suggestion was that we dig holes in the embankments of the railway. “Not on your life”, I said. “The railways will be the first target.”

We never got no Haldane shelter – we got nothing, only what the government allowed. The kind of shelter they built in the streets was built of mortar and sand – lime and sand. They just fell down. They didn’t need anything to blow them down. So we decided to get the women and children out of the town. This was before an air raid started. London had had it. Coventry had had it, and Liverpool was the major port in the country. All the shipping, all the convoys, all mustered up from here. I went to the Town Clerk, because I wanted to get the women and kids out. He hadn’t a clue, do you know that? He said “What are we going to convey them in?” “Jesus Christ”, I said, “the docks is loaded with meat wagons. They’re going to do nothing if there’s an air raid. Surely they can be commandeered.” He didn’t give no definite answer, so my committee, the NUWM, twelve men who knew their stuff about the borough, we met and agreed that we had to get the women and children out every night, out of danger. There would have been terrific casualties if we hadn’t done that.

I think as a result of the raids people were more inclined to go to work. What could you do at home. Often your windows had gone, or the roof had come off

Liverpool Teenage Girl Where we were we had shelters. You got a lot of “This is my pitch. We were here last night.” You wonder how you lived in it now, because there was an awful lot of filth. There was a lot of scabies knocking around. You were that close together, everybody had it. No one ever looked clean. You had nowhere to wash – you had no time to wash. Unless you got things done first thing in the morning, that was your lot. There was no such thing as water in the shelters. You’d bring flasks of tea or during a lull in the raid, or on a quiet night, you’d be able to run home and boil a kettle and make tea. The majority of the men and women used to go the pub next door, but they got caught there one night – there was a raid on – and they couldn’t get out.

My Mother was a knocker up of everyone for work. She’d wake the whole shelter up, I’m talking about 120 people. I think as a result of the raids people were more inclined to go to work. Absenteeism didn’t go up. I think they were glad to get to work to forget the war. What could you do at home? Often your windows had gone or your roof had come off. You wouldn’t want to sit in an empty house like that, would you.

After a while, things got that hot during the May Blitz, and we lost three in the matter of six weeks in the one house, that my older brother said to me Mum “Come up and stay with us for a while.” That was just after my sister was buried. His place wasn’t far from the Kirby Estate, well it was all countryside then, it wasn’t an estate. It was a bit safer there. He had a little Anderson shelter in the back garden. He had his family, there was a gang of us, and we’d bought a sister-in-law an’ all – honest, we were sleeping in the cock loft! But there was a big gun there and we were in the shelter one night and it went off – the noise of it! “Oh”, I said, “I’m going back home.” So I went back home and stayed on me own. Back home, what they used to do at night time, about half four, before it got dark, people would climb on wagons and they’d go to the outskirts – anywhere – to get away from it. They’d stay there the night. They’d sleep in the lorry or often they’d just sit there, singing all night, and then they’d come back in the morning. Half the time you didn’t know whether it was day or night.

I can honestly say Hitler would have got the better of us. A couple of more nights, there was no question about it. People were really scared

Liverpool Mother Our Pat, she was born in the March, 1941, just before the May Blitz. I had her, and the other little one would be two and a half, and then the two boys. In our area we didn’t have air raid shelters. They hadn’t been built. We didn’t have a garden so we couldn’t have an Anderson shelter. We used to go underneath St George’s Hall – I used to take the four of them there. But it got too much to trek down there and be half way when the sirens would go, so we started going under a railway cutting. It was where the train comes out of Edge Hill Station, and goes down and then would be coming up, ready to go to Lime Street. We used to go down the steps and underneath the tunnel, and take turns in throwing bricks at the rats. One hour on, one hour off. We had no lighting in the tunnel. We were in darkness.

People were worn down. I can honestly say Hitler would have got the better of us – a couple nights more, there was no question about it. People were really scared. They were terrified. There were ammunition ships in the docks at the time and the Germans bombarded them and all day and all night there was explosions where the ammunition ships were being blown up. And what wasn’t blowing up, our side was blowing up to save more damage. There were explosions every minute. People’s nerves were really terrible.

One night we sheltered in Cain’s Brewery. It’s Walker’s and Tetley now, but they used to have their brewery very near the Dock Road, and when they had their horses, they used to have a slipway from a road. It would come down a slope for the horses to walk down, and they used to stable them underneath the brewery. They opened it as an air raid shelter. It was very handy for us so we went there. A bomb dropped on the brewery and the top was on fire and we were underneath. We couldn’t get out.

There were about two hundred of us, children included. But luckily it was discovered there was an opening that led up another passage-way, out into a street at the other end, so we all managed to get out. But after that the wardens came round and said it was compulsory evacuation. If you didn’t allow your children to go on their own they’d be taken and you wouldn’t know where they’d gone to. A mother could go with them if she had children under five years.

They called us dirty evacuees, but we hadn’t had water for five days before leaving, so you couldn’t expect people to be clean

The morning we were evacuated, Lewis’s, Blackler’s, the whole town was absolutely raging. It was alight. It was like broad daylight in the early hours of the morning. Everything was chaos. You were put on buses, lorries, anything at all, to get you out to the safe areas. Whilst Liverpool was burning I was struggling to get on this bus, and our Jimmy and our John had their bags of shrapnel in a little canvas bag tied round their necks, and they were arguing about their shrapnel and I was hammering them for to get on the bus. Apparently I’d given the wrong bag to each of them. The conductor said “Take a couple of pieces out of one and put it in the other and they’ll be happy.”

We went to Southport. They called us dirty evacuees, but we hadn’t had water for five days before leaving, so you couldn’t expect to be clean. The only water we had was from the Mount. There was a Spring there. We used to queue up for a bucket of water, and that had to do for everything.

After a few days I had to come back from Southport to collect some clothes for the children. It was a job getting through because they had bombed Bootle and you couldn’t get a train through. When I eventually got home I found people had looted it. They’d left the furniture, but they’d stripped the dishes and all my sheets and blankets. There was a lot of looting in Park Lane, Park Road. Human nature didn’t change because there was a war on.

I went into a house in Oxford Road to do some cleaning for one of these WVS – I thought I was having a dream. You couldn’t get into the cellar for food

I had a sister who lived in Southport and she said I could live in with her, but there wasn’t the room – they had their two children and my mother and her mother-in-law. So she got me to go and stay with a lady. But I couldn’t stay there – I had to be out by 9 o’ clock in the morning and I wasn’t allowed back until half past six at night. Through a minister of the Church I moved into a large house owned by one of the Hartleys, the jam people. Christina her name was. She’d bought this house and put beds and chest of drawers, and the rooms were let off to mothers and children, like bed-sitters. There were six mothers and we had a communal kitchen. It was good because it was beautiful and clean and you had every facility for washing. She used to claim billeting allowance from the government for as many as she had in the house.

At Southport we lived like Kings. I had the newborn baby, the little one of two and our John and Jimmy. They weren’t big tea drinkers, but you still got your tea ration for your newborn baby and each child. Tea was like gold, so anybody who knew you had two quarters of tea – a pound of steak! Or a fowl! Bartering was going on. My children were as well dressed as any in Southport. You didn’t pay for the clothes. You got all the cast-offs and you gave them your clothing coupons. It was barter. They had the money, but if you had a few children you had the ration books and the clothing coupons. There was money in Southport.

Same as your sugar – you wouldn’t be using all your ration, so they’d barter it for fruit. It was very, very hard to get fruit during the war, but they had it. I went into a house in Oxford Road to do some cleaning for one of these WVS – I thought I was having a dream. You couldn’t get in the cellar for food. It hadn’t been bought during the war. It had been bought by the hundredweight before the war. She had everything that was on ration. Mind, she was very, very good. You never came away empty handed. A bit of fruit for the children, or currants, or something.

If you didn’t have any children under a certain age you were liable to call-up, a woman was. Town people, working class people went into munitions or what have you. But the well-off women in Southport dodged it by going in the WVS and these other organisations, looking after evacuees and running dinner centres, but the slaves – that was us with the little children, we went and we cleaned for them, whilst they went out to do their voluntary work. I was getting about two pounds and two shillings (11) allowance from the army (my husband was in the army) and that had to keep myself and the four children.

Royal Engineer When the raids were on in London my wife was evacuated down in…. I think it was down in Norfolk. She went to this school – this was in London – which they made into an evacuation centre and they loaded them on coaches and took ’em down to Norfolk. When they landed them in this place they unloaded them on the pavement. She had the two children, the two girls. The people who had already applied for them came along but this woman who my wife was supposed to go with, when she saw the two girls, she said “Oh no, I don’t want no children.” And she was left there. Everybody was gone and she was sitting on the pavement in this village, crying, with the two kids. No one wanted to know. A young girl about her own age walked up and said “What’s wrong? I’ll take you home with me.” She went and stopped with her for about three years. It just shows what it was like. They thought they were onto a good thing, some of them. They changed their minds afterwards.

We went to Oakham and being us we got the worst of it. We was living in bleeding stables, Mum and me

Young Woman, East London I was working at Knights, the soapworks, when we got bombed out. We got bombed out and we were living in schools, waiting until they evacuated us. We was in Russell Road school. (12) If we’d gone to that other one – the one where all the people were buried under, we would have had it. We was evacuated to Finchley. Mum and me. When we got to Finchley we knocked on the door of this house we were supposed to go and we said “Can you take us in?” She said “You can come in, but we don’t want you. We’ve got a corpse lying here.” I says to our Mum “I ain’t going in there! I ain’t going in there!” She didn’t want us anyway. She was la de dah. We had no clothes with us. Nothing. As we are walking along – we was both crying – there was a woman standing at her gate and she saw us and she says “What’s the matter?” So I said “That woman up there doesn’t want us.” So she said “You can come in here if you like.”

We used to have some good laughs with her. I was a proper coward I was, but my Mum and her took no notice. We used to make soup and take it down to the Anderson shelter – I used to be the first one in the shelter me. I used to say “I don’t know how you can sit there and eat that soup.” We used to take a bucket into our shelter and chuck it out onto the yard, on the marrows, and the marrows grew huge! At Finchley I got a job in the post office for a fortnight, but I used to drive our Mother up the wall. I said “I’ll have to get away from here, it’ll drive me mad.”

Dad used to send us money and he used to come and see us. He was working in the arsenal at Woolwich. He had it rough our Dad. He lived rough all the time, sleeping down the deep air raid shelter on Wanstead Flats. He used to walk through the foot tunnel under the Thames to go to work every morning. One night our Dad came to see us and he had a septic finger. The night the Fire of London was on a policeman came to say my Dad was in Joyce Green Hospital, where all the soldiers was. He said “He’s had a bit of an accident. Can you go over there?” We thought his hand had gone septic. Next morning we gets there and his hand’s all done up. He’d lost his fingers in the cog of this machine.

Whilst we were at Finchley Dad got this house from the Council and he went and got the bits and pieces of furniture we had left, that was in storage, and we came here, to Gresham Road.

Her Mother When we came here the bombing started again and Rene said “Ooh, I can’t stop here” and then we went to Oakham, Rutland.

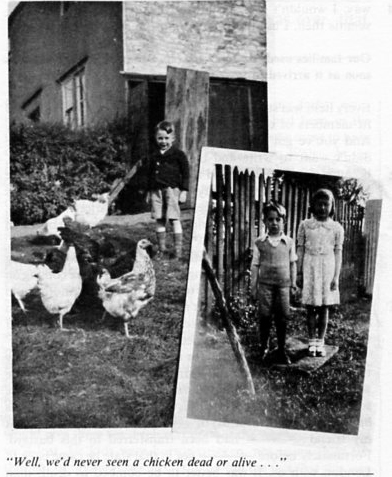

Young Woman, East London Being us, we got the worst of it. We was living in bleeding stables, Mum and me. Going to Rutland wasn’t the first time I’d seen country. We used to go to Southend, and I went ‘opping once when I had diphtheria.

Her Mother No, she had bronchial pneumonia. We went with Lil Stephens.

Young Woman, East London When we lived in the stables we had no furniture. We was sleeping on hay. It was the summer. We used to go for walks down to Cottesmore aerodrome in the afternoon and we used to have our meals in the WVS. Then we got digs eventually, but Mum decided to come home to Dad. But me, I stopped down there and stayed with someone else. I worked in the picture house in Oakham. It was a nice little picture house. It had a circle and everything. I knew a lot about the pictures because my Dad worked in picture houses before the war. I was well in with everybody down there, but it seemed to me that they were calling a lot of people up, so I said to Mr Black the manager “‘Ere, Mr Black, it seems they aren’t half calling people up. I think I’ll get myself a job in the Land Army to keep out of it.”. So I joined the Land Army

1. The first bombs to fall on Britain killed 25 Royal Navy sailors aboard cruisers on the Firth of Forth, 16 October, 1939. The first civilian casualty of an air raid occurred at Bridge of With, Orkney, 16 March, 1940. Cundy Road, Custom House, along with other East London dockland areas, did receive the first concentrated mainland bombing.

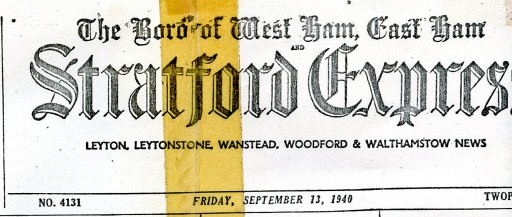

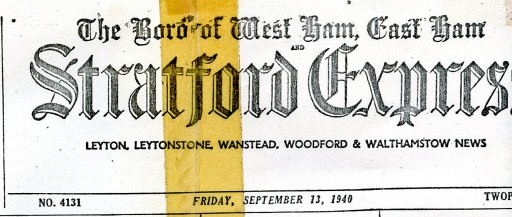

2. Curiously, virtually all books state that the London Blitz started on a Saturday evening, 7 September, 1940. But the East London Stratford Express in its report of 13 September, 1940, states that the raids started on Friday evening, 6 September.

Stratford Express, Friday September 13, 1940

Straford Express reporting that the London Blitz started on Friday, 6 September, 1943

3. Anderson shelter. Named after the then Home Secretary, John Anderson. They were a family sized shelter, built of sheets of arched corrugated iron sunk, or semi-sunk in the ground, sometimes with a turf or other topping.

4. Odessa Road: Forest Gate, East London.

5. Lord Haw Haw: A name given to several English language propaganda broadcasters from Berlin, beamed to Britain. William Joyce, of Irish-American background, settled into the role from 1940 to 1945. Captured by the Allies in May 1945, he was hanged by the British in London in 1946. Pre-war he had been a prominent member of the British Union of Fascists.

6. Jim Callaghan, at the time of the interview in 1976 Labour Government Prime Minister.

7. Clydebank Blitz was on the nights of 13 and 14 March, 1941.

8. Blackburn Street, Govan, Glasgow. Part of the then upper Clyde shipbuilding areas.

9. J.B.S.Haldane, geneticist, evolutionary biologist and Marxist. He became a Marxist and supporter of the Soviet Union and the British Communist Party in 1937. He wrote articles for the Daily Worker, including advocating large surface built communal shelters made of re-inforced concrete. His ideas were not taken up by the British Government. Similar, but larger such shelters were built in German cities, and many are still seen, intact, in Hamburg. He became a member of the British Communist Party in 1943, but left the Party in 1950.

10. The National Unemployed Workers’ Movement, a Communist Party Front organisation. Organised the Jarrow March, amongst many other activities. Dissolved in 1943.

11. £2.10 p.

12. Russell Road, Custom House, East London. Part of the then London docks areas.

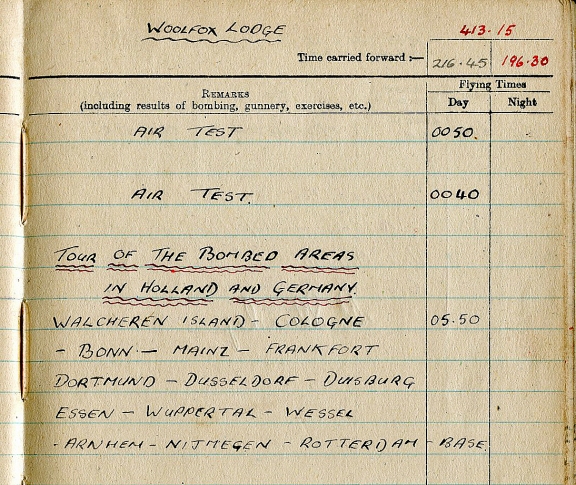

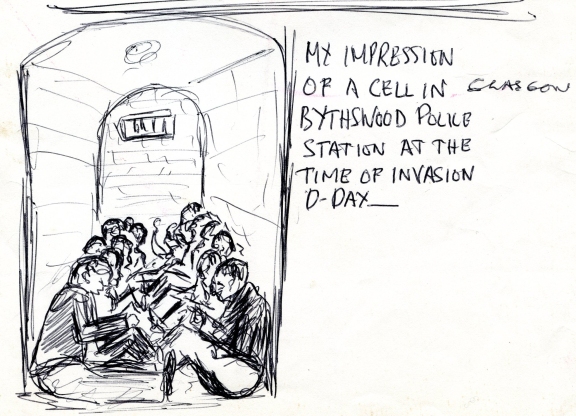

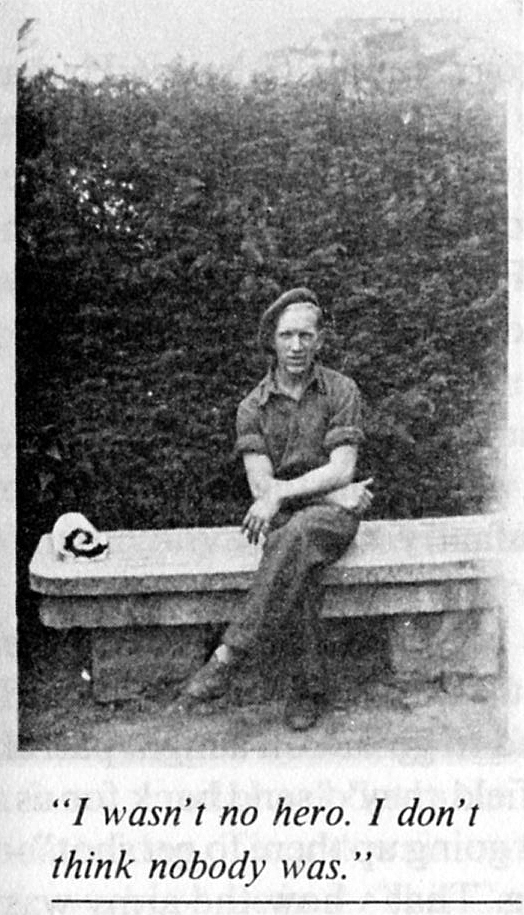

24 Disaffection of the Forces

The maximum sentence for disaffection of the forces under regulation 1AA was fifteen years. We didn’t know what to expect.

Anarchist During the war the anarchist movement was pretty well a closed shop, as of course it had to be. There was the overt activity – the open, public activity, and there was the underground stuff going on. There was the whole business of having to protect deserters and people on the run. There had to be security. And so the Anarchist Federation, as it was then called, was something that you were only invited to join. You couldn’t just bowl up, or write in and say “I want to join you.”

When I first went to Belsize Road, where the Freedom Press was, I was fascinated and I was interested. (1) I felt I had come home, inasmuch I had found people of similar attitudes. The overt activity of the Freedom group was things like public speaking at Hyde Park and publishing War Commentary, which had an uninterrupted run through the war.

All papers had an uninterrupted run through the war, with the exception of the Daily Worker that was banned for a year after 1940. Because of the invasion of France Herbert Morrison (2) decided that freedom couldn’t be extended to the Communist Party any longer, and their paper was banned until Germany attacked Russia and the Communists changed their line overnight from opposition to support of the war. They started publishing again and became the most outrageous patriots of the lot. Anyone who opposed the war was denounced as an agent of Hitler and the Trotskyists. (3) They were absolute bastards. They used to hassle sellers at Hyde Park. You’d be jostled and papers would be knocked out of your hands.

We sold the bulk of what we printed. We had good sales here in London and a very, very good and active group in Glasgow at that time. Best working class orators I’ve ever heard speaking every Sunday at Maxwell Street, in the heart of Glasgow. In the summer outdoors, and in the winter they took St. Enoch’s Hall and had big meetings there. It was the most influential working class group in Glasgow at the time amongst anti-war people.

The ILP were very strong too. It was still the time when people talked about “The Red Clyde”, and that period of the strong ILP. Besides us and the ILP, the SPGB was the other political group totally opposed to the war. (4)

In fact, they were one of the few organisations where you pretty well only had to go before a Conscientious Objectors Tribunal and say “I’m a member of the SPGB” and you’d get off automatically. They had a splendid record of getting people off and a lot of it stemmed from Tony Turner, because he would go and speak for somebody.

Stepney, London Teenager I became a socialist when I was fifteen. I was a member of the SPGB. My Father, who’d been a docker, had died so there was no political influence on me at home. I met this bloke at work who was in the SPGB, and he introduced me to them. He took me to a meeting by a man called Tony Turner, and he’s probably the greatest speaker I’ve heard in my life. He was fucking Moses.

Anarchist Tony Turner was often on Christian name terms with the Chairman of the Tribunal – “Well, Tony, what you’ve got to say about this one?” The two groups that were usually recognised were the SPGB and the Friends – the Quakers. The Jehovah Witnesses were continually turned down. I never quite understood that, except they’re a pretty intolerant bunch, and never really recognised as a proper religious body. But Tony Turner was a brilliant speaker. The story goes that on the day war broke out he spoke for about nine hours continuously in Hyde Park. One report said there were thousands of people listening to him.

We had a problem of where to put a rather special deserter who had just come out of the army to join us

As I said earlier, one couldn’t simply bowl up and join the Anarchist Federation. They sized you up for a long time. I’d been selling newspapers in Hyde Park and doing drawings and sign-writing posters, for a whole year, and I’d just started writing articles for them, before they finally decided I was a fit person to be invited to join, and then I was right in the bloody thick of it.

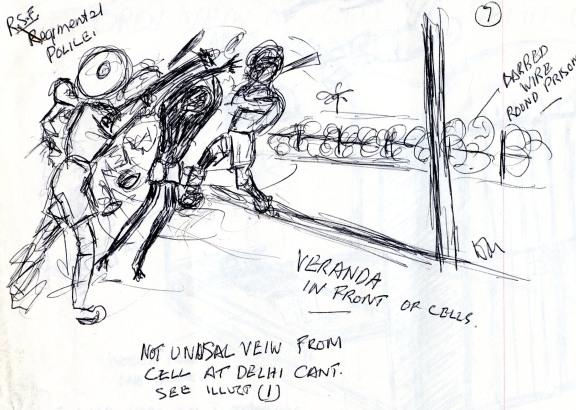

I had a nice little studio then, in Camden Town, in Camden Street, which was a very nice secluded place behind a church, with an alleyway leading to it. We had a problem of where to put a rather special deserter who had just come out of the army to join us. He was a chap called John Olday. He was of German origins who’d been in the German anarchist movement before the war and had come over here just before the war. He’d been drafted into the Pioneer Corps and was in it for a couple of years. He was a cartoonist and had been sending his cartoons to War Commentary – very, very sharp, acid and funny cartoons.

Cartoon: John Olday

The time came when he decided he could no longer stand it and wanted to pull out. So we had to give him some place to live and this little studio of mine was just right. He came and lived with me in that studio for quite a few months. He established a network of communication with dissident soldiers. He started a regular monthly newsletter – soldier’s newsletter – which was duplicated. He sent this out to a list of about two hundred soldiers. His special knowledge of the army gave him the opportunity to talk in their terms and establish rapport with soldiers which us conches didn’t have.

Besides publishing War Commentary we also turned out an unending stream of little penny pamphlets and sixpenny booklets.

In the autumn of 1944, when the State decided to attack us, I was off on a book-selling tour. We’d drawn up a big itinerary starting from London up to Bristol, up the west country, up to Glasgow, across to Edinburgh and right the way down, covering every major town. I did a sort of whistle stop tour with my little bag of samples of all our pamphlets. It was an absolute joy. I sold £500 worth of literature in six weeks! I was sending orders down and they were having to get some things back on the press because they were right out.

It was at this time that John Olday got picked up. He was carrying a typewriter home late at night and a policeman stopped him and asked him what he was doing, and where he was going, and where his card – his ID card was. He had to go down to the station and he got nabbed. He kept stumm for a long time – wouldn’t say who he was, but eventually they found out and it coincided with some things we were saying in the paper that they were objecting to.

They raided my studio and found all his stuff – the duplicating machine and discovered that letters had been circulating among soldiers. As a result of this they raided Freedom Press and because I was on this book-selling tour they found my Ration Book and they said “What’s this?” You could stay one night in a hotel without a ration book and so I was living for the six weeks without the thing and I’d left it behind for other people to pick up their rations. They also found in my studio a lovely great big sheepskin coat which I’d bought from a soldier when I had been working on the land, and had a motorbike. It was something left over from the Norwegian campaign.

As a result of them raiding my place and Freedom Press, as a consequence of picking up John Olday, the whole bloody balloon went up. By the time I got back to London I had to go into hiding. They’d nabbed three of the others. They’d picked up Vernon Richards, who nominally was the owner of Express Printers, the movement’s printing press, and John Hewetson, who was a doctor, and he was nominally the owner of Freedom Press. The third was Marie-Louise, Vernon Richard’s wife, and an activist in her own right.

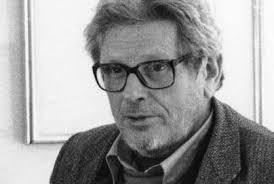

Vernon Richards

Philip Sansom

When we were attacked the amount of support we got from all sorts of directions, including people like Orwell, was astonishing

So there were the four of us. John Olday was already in nick. The maximum sentence for disaffection of the forces under Regulation 1AA was fifteen years. The Disaffection Act of 1934 had laid down two years maximum but the wartime regulations upped that to fifteen years. We didn’t know what to expect.

A few months before us, four trotskyists had been done for inciting a strike in Newcastle – the famous Apprentices’ Strike, and they’d got six months, I think, just for that. (6) And our thing seemed to be getting a hell of a lot more attention. We were anticipating two, maybe three years. Not so long before us a chap called T.W.Brown had got eighteen months on a similar charge. He lived out at Kingston and he’d produced his own anti-war leaflets. He’d actually gone around handing leaflets out to soldiers and members of the Wrens and the Women’s Airforce, and things like that. He’d given one to a Waaf who immediately went straight to the police, had been picked up and had got eighteen months. We thought: surely we won’t get less than that.

We didn’t feel at all isolated. For one thing, if you’re a member of a group, or a movement, you get this little cocoon around you and the rest of the world doesn’t exist. It’s like living in London – you have your own community and the rest of London is like a desert as far as you’re concerned. When we were attacked the amount of support we got from all sorts of directions, including people like Orwell, was astonishing. They rallied around in an absolutely marvellous way.

Freedom Press had an enormous amount of prestige at that time and a lot of affection going for it, and a lot of respect. It had grown out of the Spanish war, which was still not all that far behind, and so a lot people rallied round. I’m never going to hear anything against old Herbert Read, on account of what he did at the time. (7) He roped in all the bloody intellectuals, with his name behind us, and Ethel Manning and old pacifists with prestige like Reginald Reynolds, and a few other people like that. And he got M.Ps on the Defence Committee – Michael Foot, Fenner Brockway, Sidney Silverman – I think. The Left M.P’s joined up – Bevan joined us as a patron of the Freedom Press Defence Committee, and people like Orwell wrote, and the whole thing began to thunder. (8)

We set up a Defence Fund and we raised £2000 in a very short time, with the result that we were able to buy the services of top flight barristers. We had John Maude, who afterwards became Recorder of Exeter; Derek Curtis Bennett, as he was then. He afterwards became Sir Derek; a chap called John Burge, who seems to have sunk without trace, but was a very, very able guy. He was my bloke and spoke very well. We were also able to hire the services of someone called Seaton, who became a real right bastard of a Recorder later on. He was a right wing sod and we retained him simply to stop him being used by the other side. He just sat there looking glum and not saying a word all the time. And as a junior – nice little twist – a chap was assigned as a junior to Curtis Bennett. He’s now a Labour councillor and lives just up the road. A short while ago he advised me on some rent trouble – a little battle I was having with my landlord.

We put it forward, and it was accepted as a Freedom of Speech thing. This was Orwell’s attitude

He made it perfectly clear he didn’t agree with us about the war, but he was concerned about the freedom of speech issue. He spoke on our platforms, both before and afterwards. The Freedom Committee was kept going after the trial as a sort of alternative to the NCCL which at the time was heavily CP dominated. (9)

When I was arrested the police found that I hadn’t notified my last change of address on my Identity Card. Because I didn’t seem to have an address they wanted to hold me and I was charged on two accounts, besides the Disaffection charge. One, for not notifying my change of address and two, for being in possession of government property – the army sheepskin coat I’d bought off this soldier. I was given a month on each account, just to keep me in while they were cooking up the main charges.

I was in nick when the first hearings began in the magistrates’ court for the general charges against Freedom Press. There was quite a battle to get me bail. They fixed bail at £1000. They were prepared to accept two people at £500. I actually had three or four people in court prepared to do that, but none of them would swear on the Bible! The bloody old judge wouldn’t accept them! They were prepared to affirm, but not take the oath. There had to be an application to a Judge in chambers, who declared that it was quite illegal for the judge to have refused to accept affirmation, so I was finally let out. I was out when the main trial started.

I had already done a little bit of prison sentence in Brixton, which was a first-timers’, remand prison then. When we finally got weighed off at the Old Bailey and got nine months each we were highly delighted! We’d been expecting a lot more. After the sentencing we went in different directions. Hewetson had been in jail before, as a conscientious objector, but that doesn’t count as a criminal offence, so he was able to go to the Scrubs, which is a first-timers’prison. It was also Richards first time, and he went to the Scrubs. But I, as a second-timer, I was sent to bloody Wandsworth, which was a hell of a jail. Marie-Louise was found not guilty on a technicality.

They put me to work in the print shop. Here was I, having been done for making propaganda to disaffect the forces, actually being taught how to print

After a few weeks at Wandsworth I applied for a transfer to the Scrubs, where the others were, but instead they sent me to Maidstone, which was a lovely little nick. I had no complaints at Maidstone at all. It was mid-summer by this time. They put me to work in the print shop. Here was I, having been done for making propaganda to disaffect the forces, actually being taught how to print. I thought it was marvellous! Unfortunately I was stupid enough to write out and say this in my letters and the Special Branch were of course reading them, so after a week at Maidstone I was hurriedly sent back to Wandsworth.

I applied again for a transfer and eventually they did send me to the Scrubs. There we had a great time. There was this chap T.W.Brown, there were us three and there were about two others sympathetic to us. One was an ex-Communist.

Apart from the criminals in there, who were not a great lot, most of the chaps were deserters

There wasn’t a hostile atmosphere in there. We set ourselves up very quickly to become a kind of advisory body, and Hewetson, as a doctor, always had his ear bent to various complaints. We became quite a nice little influence.

The Deputy Governor was a young keen Rhodes scholar from South Africa, who obviously had ideas on rehabilitation of prisoners. He thought he was going to set up a sort of educational thing, for one thing, to show us up for the idiots we were. First he started off discussion groups where we’d read the daily papers and he’d pick out items and say “We’ll talk about this.” There’d be a polite discussion, but because our ideas came through it got up his nose. So he said “Right, we’ll have debates about this.” They set up debates on all sorts of issues and we wiped the floor. Hewetson was a very good speaker and the ex-communist – a little round-faced man – turned out to be a great speaker. There’d be about a hundred prisoners coming to these debates, and we won every time, hands down. The people they were putting up against us were toffee-nosed officers who’d been cashiered out of the army for fiddling funds, and this sort of thing! After about three of these debates the deputy Governor decided he’d had enough, and so he stopped them.

At the time of the trial the print order for War Commentary went up five and six thousand. The comrades in Glasgow really went to town. They had enormous meetings up there and stirred things like hell. They took a thousand, two thousand copies and sold them at their meetings. The trial happened at a time when the war was obviously coming to an end and the Allies obviously winning. Had it happened in the atmosphere of 1940 it might have been quite a different story. But by 1945 people were pissed off by the war.

1. Belsize Road, north west London. The anarchist Freedom Press was founded in 1886 by, amongst others, Charlotte Wilson, and the Russian Prince Kropotkin. It remains an anarchist publishing house.

2. Herbert Morrison, 1930s leader of the Labour controlled London County Council, and Home Secretary in the wartime Coalition Government.

3. Trotskyists. Followers of the theories of Leon Trotsky, prominent Bolshevik at the time of the Russian Revolution and founder and leader of the Red Army. Ousted during internal power struggles in the 1920’s, expelled from the USSR, and assassinated on Stalin’s orders in 1940.

4. ILP: Independent Labour Party, a British democratic socialist party founded in 1893. It was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 – 1932, and had several prominent MP’s, including Ramsay Macdonald, Manny Shinwell and James Maxton. Its parliamentary significance declined, with its three remaining MP’s going over to the Labour Party in the 1940’s. SPGB: Socialist Party of Great Britain. A Marxist party critical of Lenin and the Bolsheviks at the time of the Russian Revolution, and continuing to be critical since, of Trotsky, Stalin, etc. Still in existence.

5. CPers: Members of the Communist Party.

6. The Apprentices Strike of 1944 was led by the Tyneside Engineering Apprentices Guild, resisting apprentices being drafted into coal mines as part of the Bevin Boys. Trotskyist members of the Revolutionary Communist Party were charged for aiding them. Their role has been described as ‘advising and supporting’ the strike leaders.

7. Herbert Read, an anarchist and writer on Art, sullied his name among many anarchists when he accepted a Knighthood in 1953 for “Services to Literature”.

8. Ethel Mannin: novelist, essayist, feminist and left libertarian; Reginald Reynolds: Quaker, active pacifist, married Ethel Mannin in 1938; Michael Foot: co-author of Guilty Men (1940) and Labour leader in opposition, 1980 -1983; Fenner Brockway, active pacifist First World War, member of ILP, co-founder of War on Want and Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Labour MP from 1950; Sidney Silverman: active pacifist First World War, Labour Party activist and MP, campaigning for the abolition of capital punishment, often in dispute with his own party; Nye Bevan: Labour MP from 1929 and Minister of Health 1945 – 1951 in the post-war Labour Government.

George Orwell, in 1944 was, outside of the Left, not generally known. He had completed Animal Farm in February, 1944. It was rejected by his publisher Victor Gollancz, and also by publishers Jonathan Cape and Faber and Faber, on political grounds. It was published by Secker and Warburg in August, 1945.

9. NCCL: National Council for Civil Liberties. The Freedom Defence Committee continued to take up other cases until it folded in 1949. In the summer of 1945 the Freedom Defence Committee was as below: